To the Victor Goes the Spoils - Part 3

The recent Netflix series, ‘Death by Lightning,’ covered the life and death of President Garfield and his assassin, Charles Guiteau. A significant issue at the time was governmental corruption through the patronage (spoils) system. Guiteau himself was a disappointed job seeker - he wanted a job in the Garfield administration.

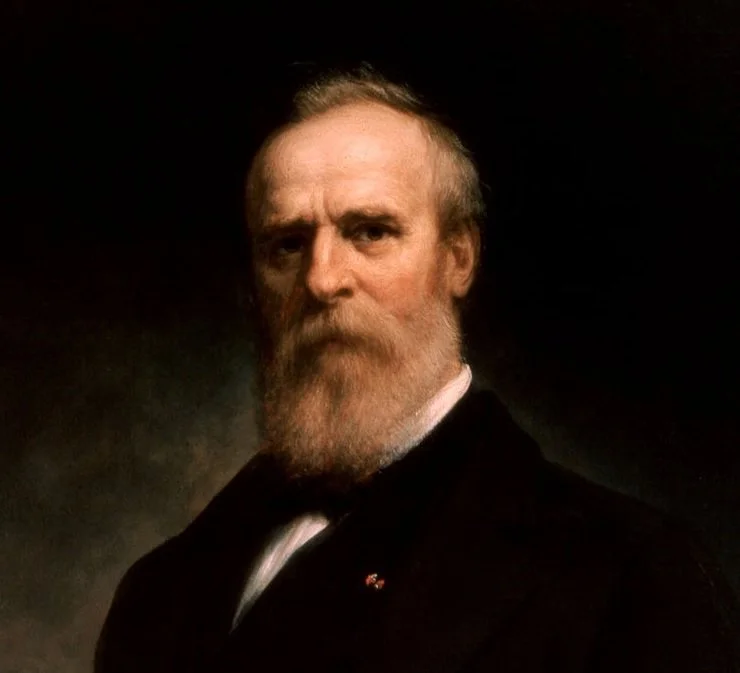

Parts 1 and 2 of this multi-part series covered the history of the spoils system, starting with its origins under President Andrew Jackson, continuing with the numerous scandals during President Grant’s terms. Public demand led to the election of a reformer, Rutherford B. Hayes, as President. This part covers the role of President Rutherford B. Hayes in starting Civil Service reform.

Rutherford B. Hayes

Rutherford B. Hayes (1876 – 1880)

Hayes was elected in one of the closest and most contentious election in our history, a topic we will cover in a future article. It took five months to determine a winner, and Hayes was not named the winner until March 1887, just a few days before the Inauguration.

Hayes ran on a platform of Civil Service reform. In accepting the Republican nomination, he first recalled the start of patronage: “More than forty years ago, a system of making appointments to office grew up, based upon the maxim, 'To the victors belong the spoils." The old rule the true rule that honesty, capacity and fidelity constitute the only real qualifications for office, and that there is no other claim, gave place to the idea that party services were to be chiefly considered.”

He went on to state that, “[Civil Service]…reform that shall be thorough, radical, and complete; a return to the principles and practices of the founders of the Government. They neither expected nor desired from public officers any partisan service. They meant that public officers should owe their whole service to the Government and to the people.”

Understanding that the President needs the support of a political party to win the election, he made this statement: “He serves his party best who serves his country best.”

Hayes also committed to a one-term Presidency, believing it would help his Civil Service reform efforts. Prior to the 1876 election, he stated: “…believing that the restoration of the civil service can best be accomplished by an Executive who is under no temptation to use the patronage of his office, to promote his own re-election…stating now my inflexible purpose, if elected, not to be a candidate for election to a second term.”

In his Inaugural Address, he supported a constitutional amendment limiting the President to a single term: “In furtherance of the reform we seek…I recommend an amendment to the Constitution prescribing a term of six years for the Presidential office and forbidding a reelection.”

Federal employees were forced to make political campaign contributions to party funds until Hayes banned them in June 1877 with an executive order: “No assessments for political purposes on officers or subordinates should be allowed.” And Federal workers cannot campaign for candidates: “No officer should be required or permitted to take part in the management of political organizations, caucuses, conventions, or election campaigns.” Hayes’s ban set a precedent for the 1939 Hatch Act. This law has an interesting history. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) was created to provide jobs during the Great Depression. In response to reports that the WPA was engaging in patronage, Democratic Senator Carl Hatch of New Mexico sponsored this bill, which limits the political activities of government employees. The Hatch Act has been amended but remains in effect today.

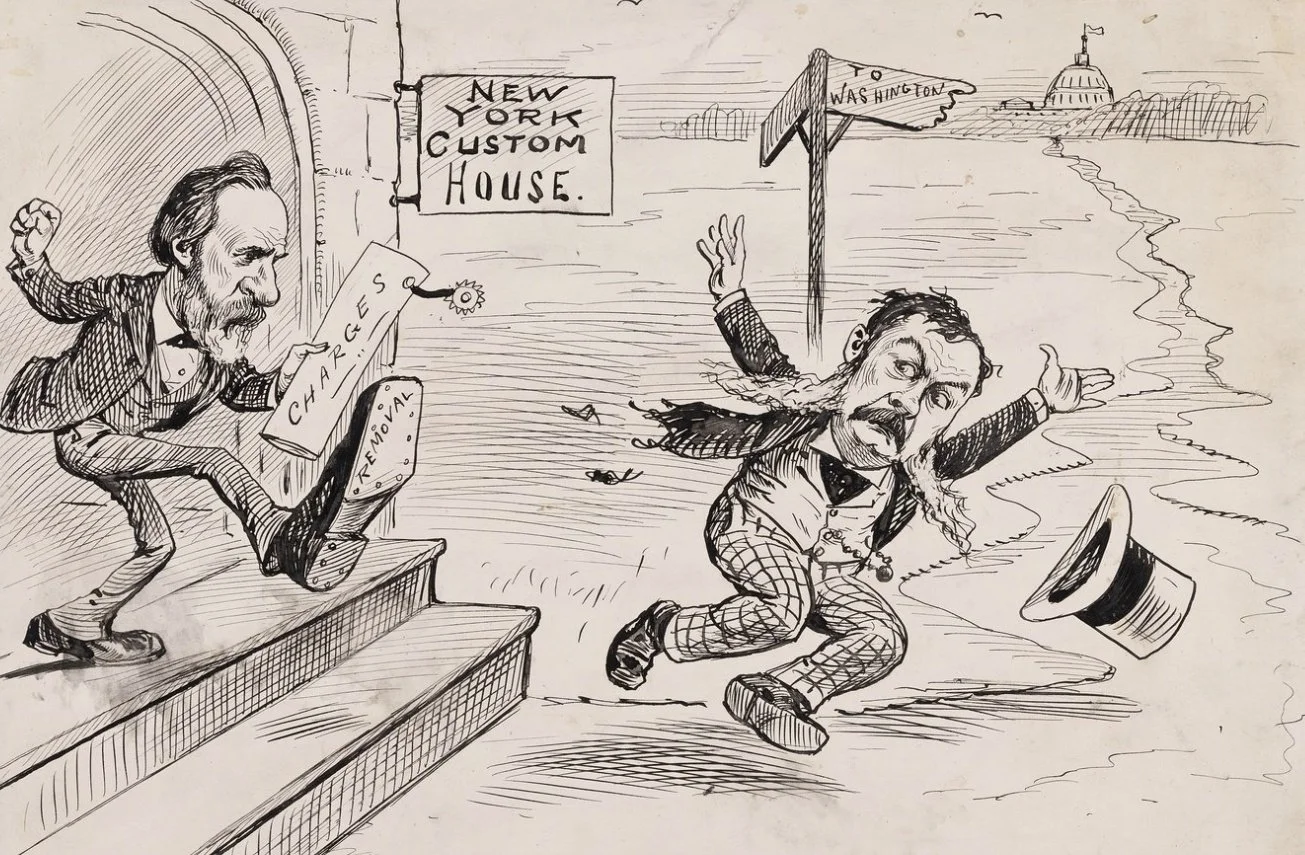

Hayes Replaces Chester Authur

At the time, tariffs were the federal government’s largest source of revenues. And the port of New York collected the majority of that tariff revenue. It was a significant source of patronage controlled by Senator Roscoe Conkling and run by Conkling’s ally, Chester Arthur. Hayes wanted to replace Arthur, stating, “The public interest requires that the Custom House be conducted upon principles of efficiency and integrity, not partisan control.” An independent study of the New York Custom House (the government body responsible for tariff collection), known as the Jay Commission, concluded that “ appointments are made not upon merit, but upon political influence. The result is a bloated payroll, with many officers whose duties are nominal or unnecessary.” In an ironic twist, as we will see in a future article, Chester Arthur will play a major role in Civil Service reform.

In 1877, Hayes nominated Theodore Roosevelt, Sr. (father of future President Teddy Roosevelt) to replace Arthur. Roosevelt Sr., a philanthropist and reformer, was known for integrity. The Senate, led by Conkling, rejected him. However, Hayes used his power to make recess appointments to fill the position, substituting another reformer, Edwin Merritt. Recess appointments allow a President to make appointments when Congress isn’t in session. Hayes used this power to bypass Senate opposition.

When the Senate reconvened in 1878, facing public pressure for reform and with the Presidential men already in office through recess appointments, the Senate officially confirmed the new Custom House officers, a victory for Hayes.

During the rest of his term, Hayes made appointments based on merit instead of party loyalty. He proposed Civil Service legislation to embed the merit system into law, but Congress did not pass any legislation.

Hayes left office, as promised, after his single term. He set the government on the path towards Civil Service reform, following his victory in the battle over the New York Custom House. But his accomplishments were not yet included in legislation.

In the next part of this series, we will learn about the assassination of President Garfield, which led to Civil Service reform.