The Power to Declare War

Background

The U.S. Constitution is based on the separation of powers. Each branch of Government, Executive, Legislative, and Judicial, can serve as a check on the other, preventing excessive power in any one branch. The Presidential Veto is one example of separation of powers. Another is the authority to enter war.

Section 8, Article 1 of the Constitution grants Congress the power “To Declare War.” Congress also has the authority “To call forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions.” Finally, Congress has the authority to “raise and support armies.”

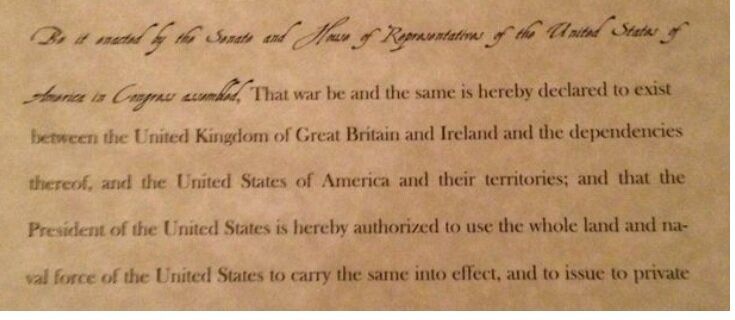

1812 Declaration of War

Meanwhile, Section 2, Article 2 of the Constitution states: “The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service of the United States”

Here we see the concept of separation of powers: Congress decides that the nation should go to war, then the President leads the nation in the execution of the war. Alexander Hamilton, in the Federalist Papers, contrasted this arrangement to the British Monarchy where the King could both declare war and raise armies.

And for the first 150+ years of the United States, it worked that way. Congressional war declarations included:

War of 1812: Senate in favor 19-13; House in favor 79-49

Mexican American War 1846: Senate 40 – 2; House 173-14 *

Spanish American War 1898: Senate 42 – 35; House 310 – 6

World War I 1917: Senate 82 – 6; House 373 – 50

World War II 1941: Against Senate 80 – 0; House 388 – 1 **

Congress has not passed an official declaration of war since then. What happened?

It started with Korea in 1950. Truman entered this war without any Congressional authority. He said that intervention was supported by the United Nations Security Council resolutions. This was the first time a President had committed U.S. forces to a war unilaterally.

The Vietnam War was authorized by the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. In response to a (now disputed) attack by North Vietnamese torpedo boats against U.S. destroyers in the Gulf of Tonkin off Vietnam, Congress passed the following resolution:

“Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the Congress approves and supports the determination of the President, as Commander in Chief, to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression.”

The Resolution goes on to allow the use of force to defend our allies in Southeast Asia.

President Nixon and the War Powers Act

In the later stages of the Vietnam War, President Nixon expanded the war into both Cambodia and Laos. In 1973, after the end of the Vietnam War, Congress passed the War Powers Act to reassert Congressional authority over foreign wars. The War Powers Act requires the President to notify Congress within 48 hours of committing armed forces to military action and, in certain circumstances, requires Congressional authorization within 60 days.

Nixon vetoed the bill stating it was unconstitutional: “While I am in accord with the desire of the Congress to assert its proper role in the conduct of our foreign affairs, the restrictions which this resolution would impose upon the authority of the President are both unconstitutional and dangerous to the best interests of our Nation.”

Congress overrode Nixon’s veto and the law remains in effect.

Congressional Authorizations

According to a Congressional Research Service report, “every President since the enactment of the War Powers Resolution has taken the position that it is an unconstitutional infringement on the President’s authority as Commander-in-Chief.” Here are some examples:

Persian Gulf War 1991: President Bush asked Congress to support the war against Iraq, not for “authority” to engage in the military operation. After Congress narrowly passed the ‘Authorization to use Military force against Iraq’, Bush stated, “As I made clear to congressional leaders at the outset, my request for congressional support did not, and my signing this resolution does not, constitute any change in the long-standing positions of the executive branch on either the President’s constitutional authority to use the Armed Forces to defend vital U.S. interests or the constitutionality of the War Powers Resolution.

After the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Centers, Congress virtually overwhelmingly passed a resolution stating: “That the President is authorized to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons…” This resolution has been broadly interpreted to allow a wide range of anti-terrorist actions, including the military interventions in Afghanistan.

Iraq War 2003: After Congress passed the ‘Authorization for Use of Military Force against Iraq, President Bush said, “... my request for it did not, and my signing this resolution does not, constitute any change in the long-standing positions of the executive branch on either the President’s constitutional authority to use force to deter, prevent, or respond to aggression or other threats to U.S. interests or on the constitutionality of the War Powers Resolution.” Obama used Bush’s rationale to support continued involvement of American troops in Iraq when he took office in 2009.

Unilateral Military Actions taken by the President

The United States has committed its military several other times without any authorization from Congress. Here are two examples:

In the 1990’s, the United States participated in various military efforts in Bosnia and Kosovo, part of the former Yugoslavia. Intervention lasted more than 60 days, but President Clinton did not seek congressional approval. He stated, “I have not agreed that I was constitutionally mandated to get congressional approval for a military action.” Several members of Congress sued President Clinton in support of their opinion that Congress was constitutionally required to approve military participation in Kosovo. The court eventually ruled that the Congressional plaintiffs did not have a reason to sue until Congress voted against continued military involvement. President Clinton also intervened in Haiti and Somalia without Congressional authorization.

When President Obama intervened in Libya in 2011, his legal staff concluded, “the President had constitutional authority, as Commander in Chief and Chief Executive and pursuant to his foreign affairs powers, to direct such limited military operations abroad [in Libya], even without prior specific congressional approval.” The administration argued that War Powers Act did not apply “...because “U.S. operations do not involve sustained fighting or active exchanges of fire with hostile forces, nor do they involve U.S. ground troops.” Obama also used drone in the Middle East without any specific congressional authorization.

Limits on Presidential Authority

The issue of the President’s power to deploy the nation’s military is still unresolved. In June, President Biden directed airstrikes against Iranian militias in Iraq and Syria. Some members raised the issue of the whether Biden needed to seek authorization under the War Powers Act, but the administration stated they have the authority to defend U.S. Personnel when attacked. Although the constitutionality of the War Powers Act may still be in dispute, Congress does hold the power of the purse, and could refuse to fund a particular military action that they oppose.

Footnotes:

* After the Mexican American War started, the House had second thoughts. It passed a resolution stating that the war had been ‘unnecessarily and unconstitutionally begun by the President of the United States.’ Representative Abraham Lincoln supported the resolution opposing the war.

** Jeannette Rankin, Republican from Montana, was the first woman to hold federal office in the United States. She voted against World War 1 in 1917, and was the only vote against the declaration of War in 1941.